Though many of us may hear the phrase “history of project management” and instinctively shy away, it’s actually a journey grounded in innovation and twists. Some of the biggest breakthroughs in construction, manufacturing, and technology all led to (or evolved from) huge shifts in the project management space.

See where the roots of project management lie to understand how they tie in to the future.

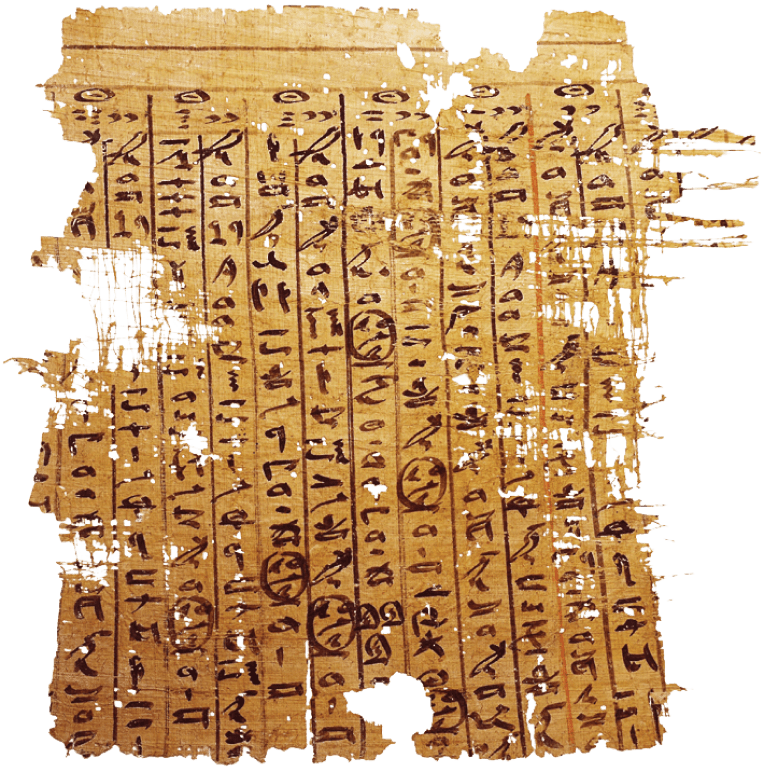

To truly see the beginning of project management, look all the way back toward ancient history. The origins of project management (and the tools most of us use on a daily basis) started with the massive construction undertakings in early civilizations.

The Great Pyramids of Giza in Egypt are widely considered the first major instance of organizing and managing projects in a formal way. This was a huge feat (even seen as impossible) requiring planning, coordinated efforts, and project timelines to successfully complete.

Look beyond the pyramids: the Roman Colosseum, the Great Wall of China — each of these projects required huge groups of people with different specialties to work together to accomplish a substantial goal.

And in order to complete these projects, people naturally started to split the end goal into numerous parts and milestones. To stay on schedule, they had to plan ahead and divide into teams working on different tasks, which had never been done on such a massive scale before. These early projects signaled that with teamwork and project planning, huge things become possible.

The next noteworthy milestone in project management history took place during the Industrial Revolution. As an era of intricate construction projects, a higher level of planning became critical, setting the stage for project management to further evolve.

In earlier years, project management was primarily about organizing large groups of people to collaborate on major initiatives. But with the rise of factories and mass production, the goal changed slightly — to do things like construct a network of railways or build a factory with assembly lines producing the same quality product again and again, an entire symphony of moving parts had to be conducted through planning and strategy.

Factories and assembly line production were, of course, breakthroughs for manufacturing. But they also fundamentally shaped project management. Specifically, the assembly line introduced the concept of breaking down complex tasks into smaller, manageable steps, a hallmark of modern project management. And today, breaking down tasks is still a signature piece of popular methodologies, like Waterfall and Agile.

During the Industrial Revolution, huge building accomplishments were completed, from the First Transcontinental Railroad in the United States (completed in 1869) to the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. Like some of those earlier construction projects, these required planning, coordination, and teamwork, but on a more advanced scale.

Though modern project management techniques weren’t at play yet, these events played a crucial role in shaping the evolution of project management concepts. They highlighted the need for structured planning, resource allocation, coordination, and communication to manage increasingly complex and large-scale endeavors during the Industrial Revolution.

Before we discuss those familiar methodologies like Agile and Waterfall, the first formal management strategies blossomed in the late 19th to early 20th century, especially as Frederick Winslow Taylor (known as the “father of scientific management”) introduced his principles of efficiency and time management in the workplace. Taylor’s main focus was on the manufacturing process, but his principles were a precursor for modern project management concepts, too.

For Taylor, the goal of all management is maximum prosperity for the employer and each employee. In other words, project management should benefit everyone, not just one side or the other — thus, collaboration and communication are essential.

Taylor’s various principles come together into Taylorism, the science of delegating and dividing tasks between employees to increase efficiency. Taylorism, though efficient, has its flaws, particularly the way it treats employees as nothing more than cogs in a great machine. But on a basic level, Taylorism explains why teams have specific procedures and processes for tasks, delegate responsibilities and share work, break large projects into subtasks, and monitor performance. And in time, Taylorism would be the basis of methodologies that allowed for changes and flexibility, like Gantt charts and Kanban boards.

Taylorism didn’t recognize one key piece of the project management puzzle: what happened when the tasks on each person’s plate started to impact the others — if one was held up, how would the team move forward with the others? If one part of the project needed to shift, would it have a domino effect on other areas?

Between 1910 and 1915, Henry Gantt set out to create a solution for these “what-if” questions. He created the Gantt chart, effectively a horizontal bar chart with project schedules and timelines. These were visual representations of a project’s schedule, tasks, and progress, which allowed managers to better plan and allocate resources. Unlike Taylor, who focused on efficiency above all else, Gantt prioritized people in addition to efficiency — by showcasing overlap and dependencies, managers could better delegate and support team members in completing projects.

Gantt increases visibility into bottlenecks and dependencies, giving project owners the opportunity to predict issues in advance. In turn, this has a downstream effect of preventing delays and missed deadlines. That’s why the Gantt chart is especially useful for large-scale projects, and was even used to plan the process of building the iconic Empire State Building.

The first Gantt charts were hand-drawn, which was challenging because one change would require you to remake the entire chart. When the computer and programs like Excel came about, technology elevated the Gantt chart to be easy to update, and today, Gantt charts are a core digital feature of almost all project management softwares.

Gantt was the first real formal visualization strategy for planning projects. And though Gantt was successfully being used across multiple industries (including by the American army during World War I) for timeline planning and resource allocation, for some companies, thinking through a workflow in stages made more sense. Project management evolved over time because people had more specific needs for planning, and created new solutions (often built onto those that came before). So while many people continue to use Gantt charts, others wanted to create a visual workflow planning system where you could move tasks from one ‘status’ to the next in real time.

Enter kanban (Japanese: 看板, meaning signboard or billboard). Taiichii Ohno originally developed the kanban for Toyota automotive in Japan in the early 1940s. Ohno created kanban as a direct competitive strategy responding to Henry Ford’s mass production model. Kanban was a simple planning system to optimize work and manage inventory through each stage of production. With kanban, teams were able to visualize the flow of work from start to finish and limit the tasks currently in progress, ensuring a smoother transition of work from one stage to the next.

Years later, people started to think the kanban methodology could work for more than just factory production. In 2004, David J. Anderson was the first to apply the concept of kanban to IT, software development, and knowledge work. He built on numerous project and production methods to identify the kanban method for knowledge work, with concepts like pull systems, querying theory, and flow.

The cover of the original published work outlining the PERT — this one is particularly interesting because it highlights the name change from “Program Evaluation Research Task” to “Program Evaluation Review Technique.”

A photo of four out of five founders of the PMI. The five founders, James Snyder, Eric Jenett, Gordon Davis, E.A. "Ned" Engman and Susan C. Gallagher, came together for the first formal meeting at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, on 9 October 1969, before filing the PMI Articles of Incoporation a while later in Pennsylvania.

Now that there was a formal professional organization and book of knowledge in place, people focused on identifying the best ways to finish projects and collaborate. New and more collaborative project management methodologies started to develop, and three major methodologies came out of this time period: Lean, Waterfall, and Agile. Each is used for a specific purpose, and was born out of the shortcomings of a previous methodology. The more important a specific need became, the easier it was to create a new collaboration method to address it.

While the waterfall method requires you to complete each step before moving to the next, the Agile method allows you to work on components simultaneously and incrementally, allowing teams to adjust processes and stay flexible, especially with changing priorities. Surprisingly, the Agile methodology wasn’t officially documented until 2001, so it’s a more recent development many teams use today. And as a descendant of those previous methodologies, Agile incorporates their best components very successfully: over 70% of U.S. companies are now using Agile.

An original screengrab from the 1984 version of Microsoft Projects.

Lotus 1-2-3, at one time the golden program for creating spreadsheets.

After so many new project management methodologies emerged in the 1900s and local project management tools started to be commonplace in the early 2000s, the next natural evolution was bringing teams together to collaborate in real time online. From their earliest explorations to being fully developed and used around the world, the internet and the cloud transformed project management.

In the 1960s, computer scientists started working on the “Advanced Research Projects Agency Network” or ARPANET, a very primitive version of the internet.

Though the internet’s roots started in the ‘60s, its official birthday is January 1, 1983. In the 1980s, home computer use started to blossom, and by the ‘90s, people were using Web 1.0, the first publicly accessible version of the World Wide Web. It was a static, read-only version of the web, where users mainly could view and read content — a much less interactive and collaborative version of today’s internet.

In the early 2000s, broadband internet access through DSL and cable allowed people to access the internet at faster speeds, and it grew like wildfire. In 1996, approximately 45 million people used the Internet; by 2004, the number rose to between 600 and 800 million users. And as the internet took off, project management went online.

With online project management tools, information was always accessible. They also solved some of the core challenges that had, historically, always accompanied managing projects. Instead of manually having to recreate paper project timelines for one shift in scheduling, additional ask, or delay, updates became instant and effortless online. Project management became more accessible with digital storage, and even became more secure with the cloud replacing traditional on-premise systems.

Lawrence Roberts, the first person to connect two computers, worked with scientist Leonard Kleinrock to develop computer networks at ARPA. In 1969, the two developed the first packet-switching network and successfully used it to send messages to another site, and the ARPANET, forefather to the internet, was born. Originally, it was only seen as a tool for academic engineers and computer scientists, and linked departments at several American universities.

Project MAC IBM 7094, 545 Tech Square, 9th Floor

The cloud started, in its initial form, when the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) gave researchers at MIT funding for Project MAC. This funding came with multiple requirements, the most important of which was an emphasis on collaboration.

Researchers needed to come up with a way for multiple people to use a computer simultaneously. Eventually, the researchers came up with a large (now, likely seen as archaic) computer with reels of magnetic tape for memory — and it became the precursor for cloud computing, functioning as a primitive cloud with two to three people accessing it.

This precursor for cloud computing paved the way for future project management tools being fully cloud-based, with multiple people collaborating from afar in real time — it showed that even in the cloud’s earliest stages, the need for collaboration was seen as highly critical.

On an implementation level, cloud-based project management tools had huge benefits: cost savings, less hardware and installs, faster software updates, more user-friendly and easy to start with than other programs, connectivity with other tools, and the ability to work from on-the-go instead of just at the office. Tools like Jira and Pivotal Tracker built on the agile methodology and brought it to the cloud-based, digital age, revolutionizing the way people were able to manage projects as a team.

And later, software tools like Asana, ClickUp, and Notion emerged between 2008 and 2018 to bring more of the team into the fold (instead of only the project manager using the software) and make real-time collaboration more accessible. These tools offered options built onto the roots of project management, like instantly updatable kanban boards and Gantt charts, or templates for methods like waterfall and agile.

Project management has evolved over time, and will continue to change in the years to come. In the present day, there are hundreds of project tools, all built on that rich project management history. From the early paper-based tool stack (papyrus scrolls, ink, and hand-drawn Gantt charts), to digital software used today, project management always set out to solve specific workflow problems. And now, a new era of project management is beginning — and with it, new challenges to solve.

One of the biggest of these challenges has been time wasted and manual effort. As project data migrated to online digital tools, teams started to spend more time chasing information and keeping those tools up-to-date than actually building or creating. Knowledge workers waste one hour a day digging through cloud storage systems, scouring message systems, and cycling through tabs — that’s 250 hours in a year, or over a full month of work.

Artificial intelligence is going to change that. Research from Gartner predicts that 80% of today’s project management tasks will be eliminated (translation: automated) by 2030 by AI. And with the rise of powerful language learning models (LLMs) like GPT-4, those innovations are quickly drawing closer. Beyond the text generation solutions currently on the market, AI paves the way for building decision engines that handle all the manual work of project management autonomously. Someday soon, project management will become an automatic process happening in the background, so teams are always up-to-date with current information and accurate project planning without the hours of work.

According to the Harvard Business Review, key areas of project management will change with AI: better project selection and prioritization; support for project managers; improved and faster project definitions, planning, and reporting; virtual project assistants, and more. For example, a product team will no longer need to worry about triaging bugs or refining backlogs. In short, teams won’t have to spend their time on the manual project management work that drains a significant amount of bandwidth today.

Essentially, project tools will move beyond just a place where teams log and maintain project data themselves. Instead, autonomous project tools will empower teams to make strategic decisions and build incredible things, without being bogged down manually managing projects.